A presentation on documents inside statuettes

From around the 8th and the 9th century, icons, especially statues, were submitted to consecration rituals (aka as the so called “open eyes ritual”) to make them come alive. According to the earliest written literary sources and archeological discoveries on this practice, it seems that in addition to the consecration ritual itself it was usual to put things inside the statues (in the “belly” fu 腹) a variety of items such as sutras, dharanis, prints, pearls, materia medica, cloth pieces, a list of donors, and so on . In Japan and in Korea, many such Buddhist statues dating from the 13th century onward– for reasons of repair and restoration – have been opened and their insides analyzed and studied in the past few decades. Curiously enough, this kind of field work and research have never been done in Mainland China and we have only some vague historical testimony about the inside contents of statues and minimal evidence about the same practice and procedure in China. An international research program conducted by the EFEO began in 2002 to catalogue three statue collections with a total number of some 3000 pieces. Nearly all these Chinese statues come from Hunan Province, more precisely from the central part of Hunan (delimited in the south by Shaoyang 邵陽, in the north by Yiyang 益陽, in the east by Ningxiang 寧鄉 and in the west by Xinhua 新化). Like the Buddhist statues elsewhere in East Asia, these Hunan statues contain items like written documents (a kind of “consecration certificate” with a precise address, identity of statue, of donors and sculptors, also indicating date and reason of consecration), materia medica, talismans, and paper money. The oldest one is dated to the 17th century, the newest to the beginning of 2000. Hunan statues represent not only Buddhist and Taoist deities, but also local deities, ancestors and religious masters. They do not belong to community religious establishments but to domestic altars, giving us for the first time the possibility to examine familial worship and local religious practices. We examined three of these “consecration certificates” dated respectively to the end of 19th century, the beginning of the 20th century and a last one to just before 1949. By chance, they also contain economic data…

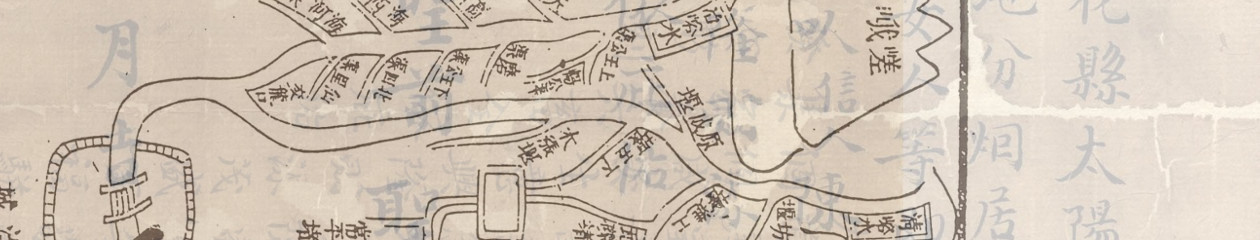

Presentation of Ningxiang County religious

establishments’ registration forms

From the end of Qing dynasty to the early years of the Republican government, many laws, rules and edicts were promulgated to control temples, monasteries and shrines (miao si guan 廟寺觀). For instance, from1915 to 1936, the Republican government very clearly issued a series of administrative rules aimed at registering all religious establishments as well as their religious staff and their property, including lands, buildings, liturgical instruments, and so on. One point, the obligation to open schools in temples (miaochan xingxue 廟產興學), has been interpreted differently by scholars: some of them have seen in this rule the wish to destroy temples and transform them into schools that would profess “normal” education, while others prefer to see in these rule and edicts the Republican government’s wish to promote education throughout China. In fact, most studies have reached their conclusions on the basis of written rules and laws, official statistics and unfortunately far too few personal testimonies and primary source documentation.

During our fieldwork trip to Hunan in 2004, James Robson and I fortuitously had the opportunity to conduct research in the Bureau of the Archives of Ningxiang county 寧鄉縣, and acquired permission to photo documents related to this issue. We found in this Bureau’s archives 749 registration forms dating from 1940 and 1941, that provide an inventory of 9 cantons’ religious establishments in Ningxiang county and thus the possibility of learning the exact number and identity of the religious establishments in this county. In fact, most religious establishments appear to have been functioning ancestral halls (citang 祠堂).

This project is still in the exploratory stage and for the time being it is still difficult to draw definitive conclusions. But these archives present very concrete economic data on the value of these ancestral halls’ estates, the amount of their rents and taxes, the name of the halls’ managers, the names of the sharecroppers and other tenants, etc. There is no doubt that by combining our findings from these registration forms with additional information from new fieldwork as well as from other local sources like genealogies and local religious statuettes (and their databank), in the future we shall be able, to establish a detailed account of the economic aspects of Ningxiang’s local religious establishments.