I am an anthropologist primarily working on Chinese religion in its more contemporary manifestations. However, some of my projects do require me to work with texts from pre-modern periods (e.g. ritual protocols from early China and writings on popular religion from the late-imperial period). While preparing for this workshop I first thought of finding a text relating to popular religion (e.g. a stele inscription on the founding or the repair of a temple), but eventually decided on this text due to its intriguing and exotic nature (most likely to be unfamiliar to most people working on late-imperial China). The text I chose is a series of minutes of the Chinese Council of Batavia (吧城華人公館 / 吧國公堂), from the year 1852 (April 23 – November 26), relating to investigations into the mutual accusations between a married couple that eventually led to the Council granting them divorce.

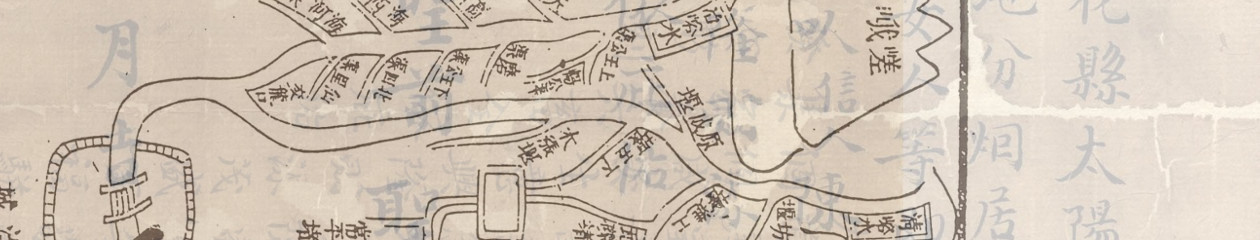

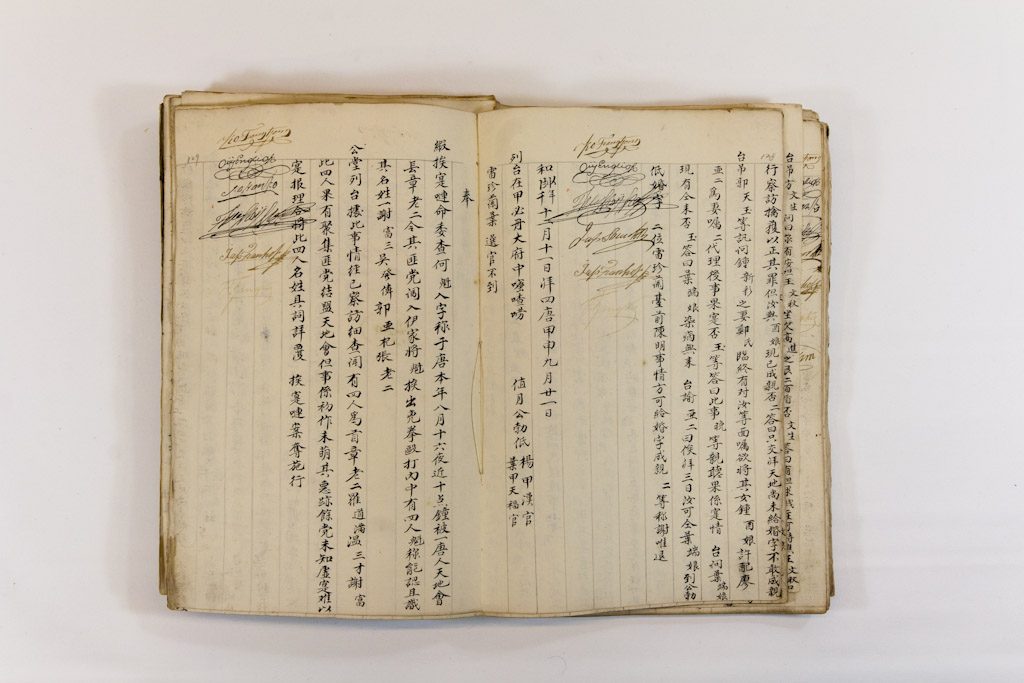

Minute in Chinese (http://www.kongkoan.nl/gallery/nggallery/kong-koan-gallery/minutes-in-chinese/ )

Minute in Chinese (http://www.kongkoan.nl/gallery/nggallery/kong-koan-gallery/minutes-in-chinese/ )

The Chinese Council of Batavia was a semi-self-governing institution set up by the Dutch colonial government in Dutch East Indies for the purpose of overseeing affairs relating to the Chinese population in the colony. The Council members were constituted by the top leaders of the Chinese community who held official titles (e.g. Majoor, Kapitan, Luitenant) and who were appointed by the Dutch colonial authorities. The Council met on a regular basis in the Chinese Council building to go over cases brought by the Chinese in Batavia (similar to a county-level magistrate’s court on mainland China). The Council would conduct hearings by summoning the different parties of a legal case (the plaintiff, the accused, witnesses, lawyers, etc.) and pronounce their verdicts. These cases related to civil affairs such as financial conflicts, divorce, witch-craft accusations, etc. Sometimes a more complicated case would drag on over many months because certain key person could not appear in front of the Council or because of other complications (as exemplified by the case I chose for the workshop).

These Chinese Council minutes have been transcribed and published in a series of books entitled公案簿 (Records of Legal Cases) within the series entitled 吧城華人公館(吧國公堂)檔案叢書, compiled and edited by a team of Chinese and Dutch scholars (侯真平, 吳鳳斌, Leonard Blussé, 聶德寧) and published by the Xiamen University Press (廈門大學出版社).

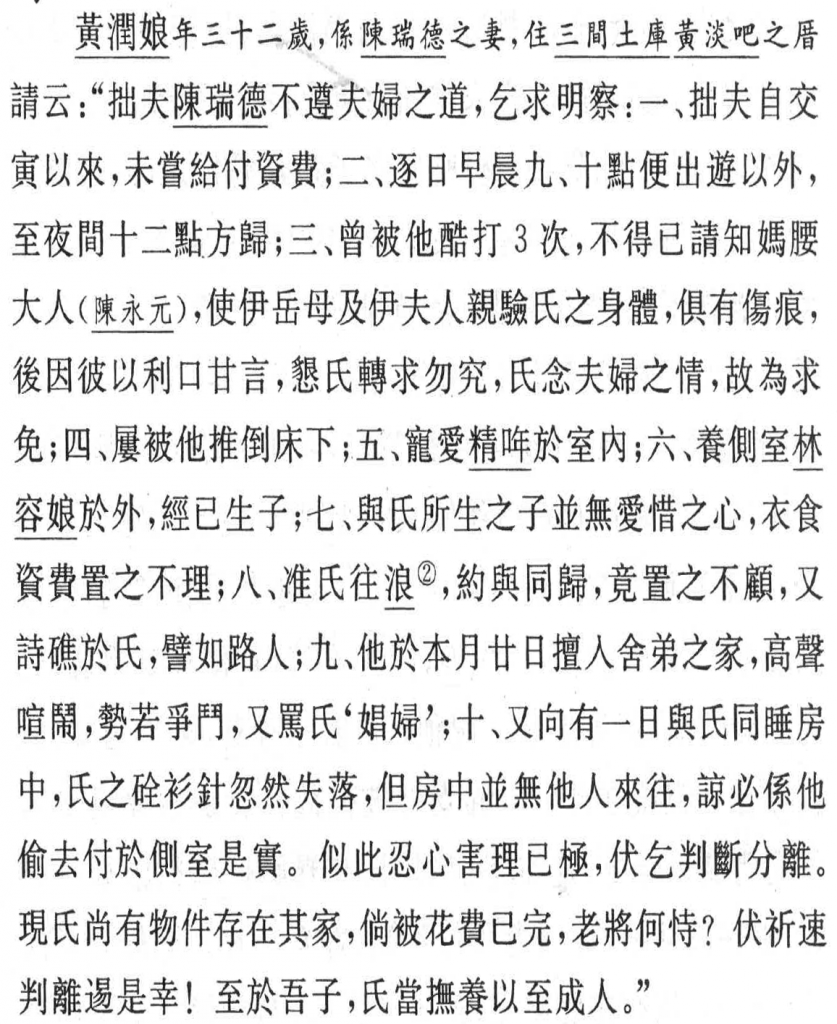

Below is an excerpt from the text (p. 61):

All of the hearings and decisions were recorded as Council meeting minutes in literary Chinese (wenyan), even when the original languages used during the hearings could be a mixture of languages (most commonly southern Fujian dialects 閩南話 but most likely also some Hainanese, Cantonese, Teochow, Malay, Dutch, Javanese, etc.), depending on which linguistic community the person involved came from. Because of this complex linguistic environment, many words in these minutes are hanzi (written Chinese) transliterations of these different languages. Some examples include 媽腰for the Dutch word ‘majoor’ (the title of the highest office granted to a Chinese), 甲必丹for the Malay word ‘kapitan’ (derived from Portuguese ‘capitao’ and Dutch ‘kapitein’, referring to appointed officers in charge of Chinese affairs), 梁礁 for the Dutch word ‘notaris’ (meaning notary), 峇峇 for the Malay word ‘baba’ (referring to Chinese men born and raised in Dutch East Indies), 字 derived from southern Fujianese meaning documents, etc. There are also Chinese transliterations of place names such as 北加浪 for Pekalongan (a settlement on the northern Java coast), etc. These strange words apparently presented a lot of difficulties for the participants of the workshop since I did not provide a glossary for them. But I deliberately refrained from providing a glossary in order to test the participants’ threshold of tolerance for unfamiliar language and knowledge while reading a piece of primary-source document (see appendix for the list of questions on the select text for the workshop participants). Mercifully, the compilation volume has a full and detailed glossary for all the local terms (almost 50 pages long!). This glossary helped me understand the documents when I first came across them, and it helped us through the workshop with frequent utterances of ‘oh’s’ and ‘ah’s’ as the glosses for strange words were revealed.

A tour of the visual materials on the website dedicated to Chinese documents of the Dutch colonial era (http://www.kongkoan.nl/), especially those produced by the Chinese Council in Batavia, was very helpful for the workshop participants to visualize and imagine a world very different from their own and very different from late-imperial society on the mainland. Indeed, this world of ‘the Chinese in colonial Dutch East Indies’ was so alien to people working on late-imperial China that quite a few workshop participants emphatically proclaimed that ‘This was not China!’ (even when the people involved were mostly ethnically Chinese and the spoken and written languages were mostly Chinese). Perhaps it is not so important whether or not that was China; rather, these documents alert us to the incredible diversity of lived experience and sociocultural practices amongst the Chinese during a time of great mobility, a time when China as a geographical entity had very fluid boundaries.

Appendix 1 : Appendix 1 Questions for the workshop participants

Appendix 2 : Appendix 2 Chinese Records from outside China by A. Chau

Appendix 3 : Material from the Friends of the Kong Koan Archive: http://www.kongkoan.nl/ (Kong Koan, Chinese Council of Batavia/Jakarta).

http://www.kongkoan.nl/gallery/nggallery/kong-koan-gallery/majors/

http://www.kongkoan.nl/gallery/nggallery/kong-koan-gallery/majors/

The EFEO thanks the Foundation of the Friends of the Kong Koan archive that gave the permission for the reproduction of the two images.